The First Women to Climb Mont Blanc

We know the names of the great forefathers of mountaineering, who marked the history of Mont Blanc: de Saussure, Balmat, Paccard

but two women also achieved this feat over the course of the 19th century. The most well-known is undoubtedly Henriette dAngeville, who climbed the summit in 1838, but we often forget the other pioneer, Marie Paradis, who took a step on the roof of Europe nearly 30 years earlier. Two women who had almost nothing in common, but who nevertheless shared one thing: they both conquered the highest summit in Europe.

A Country Girl

Marie Paradis was most likely born in Chamonix in 1778. She was born into a family of modest means and worked as a maid at a nearby inn.

She lived near Chamonix, in a hamlet called Bourgeat, which is found in Les Houches. She lived with her daughter-in-law, from the time that her son, who had been born out of wedlock, moved to Paris and was never heard from again. The two women lived modestly in a two-room house, made up of a kitchen and the bedroom that they shared. The house was simple but comfortable. A large fireplace stretched across the main room. A wardrobe, two beds, two trunks, a table, and two chairs made up the entirety of their furniture, not counting a stove for the harsh winter evenings.

Portrait of Marie Paradis (Unknown Artist, 1830)

Residing in the valley, she followed the news and rubbed elbows with a significant number of guides. At the turn of the 19th century, the summit of Europe had already been explored. Horace-Bénédicte de Saussure had indeed completed the climb in 1786, on August 16th, to be precise, accompanied by Dr. Michel Gabriel Paccard, who practiced medicine in Chamouny, as it was spelled at the time, and Jacques Balmat, a glacier adventurer who worked as a guide in his spare time. Marie was a friend of the latter, a detail which would lead to the origin of the first female ascent of Mont Blanc.

An Aristocrat Fascinated by the Mountains

The other great adventurer was Henriette dAngeville, a young lady totally in love with nature and mountains. She was born in 1794 to a noble family who lived in Semur-en-Auxois. During the Revolution, her family was forced to move, as her father was arrested, and they settled in Le Bugey, in Ain. As an independent young lady, she loved the mountains, but also had a fondness for city life. She often went on many trips to Paris, Lausanne, or Geneva. Over the course of her life, she completed numerous climbsmore than 20and didnt leave anything to chance. Before climbing Mont Blanc, she made preparations with minutia. She read different accounts written by her predecessors, contacted a doctor to help her prepare physically, and even had a special climbing suit made that was adapted to the conditions of the place.

Henriette dAngeville in her mountaineering suit. (J. Hebert, 1830)

This outfit made an impression on the minds of the time. It was made of :

- flannel long underwear; - two men's shirts; - two pairs of woolen stockings and two others of silk; - two pairs of waterproof shoes with cleats; - a pair of plaid double-layer wool trousers; - a loose blouse of the same material; - a tartan; - a boa; - a pair of knitted fur gloves, another fur; - a fur trimmed coat; - a flannel hat; - a straw hat; - a black velvet mask and sunglasses with very dark blue lenses.

She also carried a notebook where she would record her thoughts throughout her journey and some other equipment - salts, alcohol, knives, a lighter, a small coffee pot

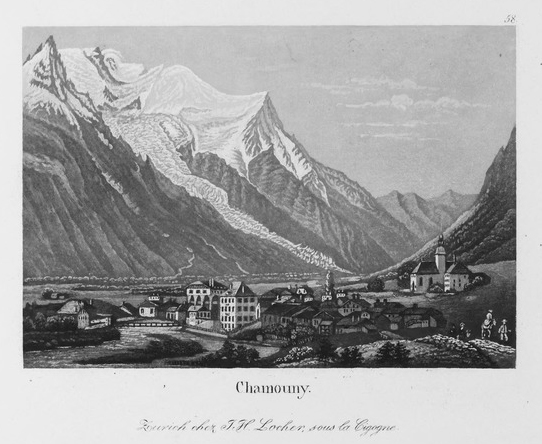

Chamouny in the 19th Century

In this era, Chamonix was a village of very reasonable dimensions that drew more and more adventurers fascinated by the massive mountains, still magical places for the inhabitants. The small village, nestled in the hollow of the mountains, was opened to tourism in 1741. The arrival of two English adventurersSirs William Windham and Richard Pocockechanged the idea of what the summits were. These men highlighted the marvels that one could view at the heights of the mountain and characterized it as a place to be explored.

They studied the Sea of Ice Glacierwhose name was their invention and replaced the name of Glacier of the Woodsand opened the doors of the village to other adventure lovers. In this manner, numerous scientists discovered the mountain, and some, the more daring, wanted to conquer the summit. The local guides, who until then had kept themselves busy hunting ibexes and crystals, accompanied the explorers to the peak. After countless attempts, Mont Blanc fell into the hands of H.B. De Saussure and his companions. This ascent made a lot of noise not just in the valley, but also in Europe. Climbers had arrived from everywhere and each had their turn to try to reach the summit. Many were failures. Over time, the mountain began to see more and more phases of tranquility. However, Mont Blanc continued to fascinate people, and the guides continued their work with climbers, some of them more experienced than others. The first solitary climb took place in 1808 with the local guide Joseph-Marie Simond. Five days later, it was Marie Paradis turn. A tragedy occurred in 1820. Dr. Hamel and his caravan of guides were lost to an avalanche. Then it was Henriette dAngevilles turn to climb the snowy peaks in 1838. In the meantime, the company of guides was created in 1821.

The village developed rapidly from 1741. Many hotels opened. The number of tourists grew and reached, in 1783, the shocking number of 1500 people, when only 40 years earlier, not a single visitor had stayed there. In 1770, lHotel dAngleterre (The England Hotel) was inaugurated and received Saussure before his ascent. Henriette dAngeville stayed at lHotel de LUnion in the center of town. Marie Paradis worked for one of these establishments. In 1850, the small village became a significant tourist attraction with 9 hotels and more than 5000 visitors.

The village center around 1830 (Artist Unknown)

Climbing the Damned Mountain

The first woman to complete the ascent was Marie Paradis, trained by the guides, a bit against her will. Knowing how to climb Mont Blanc was a way to earn money. She, of course, needed money, and when two guides names Balmat and Payot proposed that she climb with them to later be able to accompany tourists to the peak, she didnt refuse. Alexandre Dumas offers posterity to Marie Paradis and permits us to know what happened. He redacted the narration of her ascent to the summit.

Marie Paradis, peasant of Chamonix, was the first woman to reach the summit of Mont Blanc July 14, 1808

The old woman from Chamonix recounted her ascent with exemplary frankness: I was at work when some local guides, under the orders of Jacques Balmat, came to tell me, Marie, youre a good girl who needs to earn money. Come with us, well lead you to the peak, and after that foreigners will want to see you and give you gifts. That decided it, said Marie Paradis, and I set out with them. At the Grand Plateau, I couldnt go any further

I was very sick

I laid down on the snow. I was huffing and puffing like a hen that is too hot. I was given an arm on each side and was pulled along, but at Rochers Rouges, there was no way to continue, and I told them, Ficha mé din una crevasse et alla ô vo vodra You must go to the end, replied the guides. They took me, pulled me, pushed me, carried me, and finally, we arrived. Have you seen it up there? On the peak, I couldnt see clearly, I couldnt breathe or speak; it was very white, up there where I was, and very black down there where we looked.

As for Henriette, the climb was totally different. She wrote her impressions along the way. She left Chamouny on September 3rd, to follow the same itinerary as Saussure

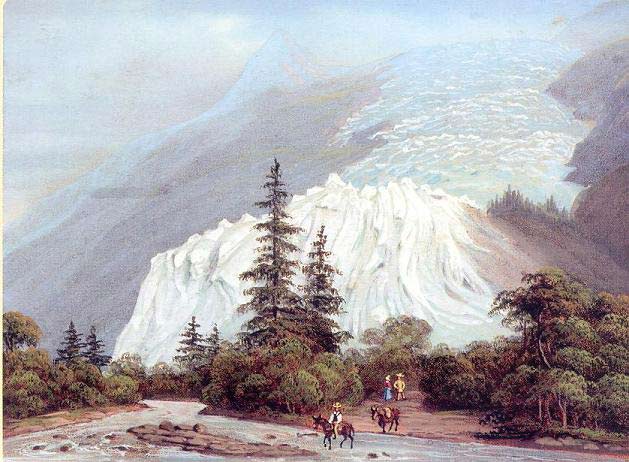

She got up at 4:30 am and ate breakfast with her guides, J. Couttet, F. Desplan, A. Tronchand et, P.J. Simond, M. Favret, and her porters. Before leaving, she checked her heartrate- 64 BPM- and after a prayer, she set off to Mont Blanc, by way of the Bossons Glacier.

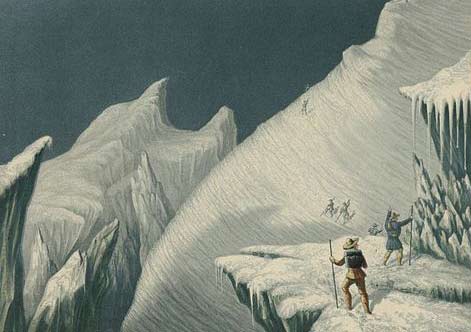

The Bossons Glacier (Artist Unknown, around 1830)

She made it to Pierre-Pointue by 6 am and then passed Pierre-a-lEchelle at 10 am. The ascent went smoothly. The weather was good and Henriettes heartrate was stable74 BPM.

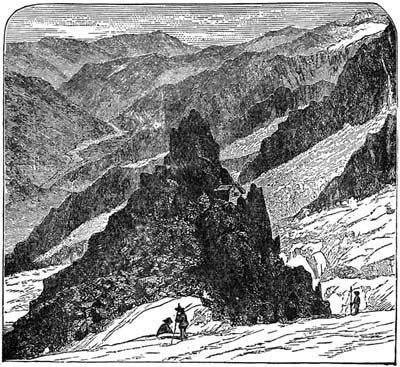

Four hours later, the group arrived to Grands Mulets. It would be the first stage of the ascent. The group set up camp and spent the night in the heart of the Bossons Glacier.

The Rocks of Grands Mulets (Image from the book "A Tramp Abroad", by Mark Twain, 1880)

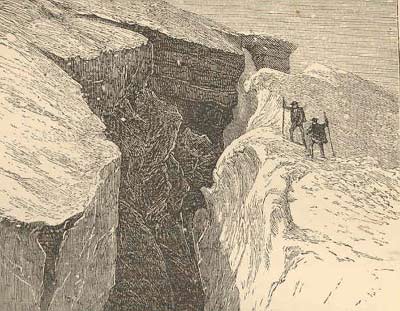

Henriette didnt sleep much on the rocks and her heartrate wasnt as stable as before. Its true that she was at an altitude of 3050 meters. The group set out towards the summit. They took a break at Grand Plateau.

Grand Plateau Crevice (John Tyndall, 1876)

Henriette started to feel fatigued and the climb was difficult. Kidney pain and an accelerated heartrate (139 BPM) slowed her down, but the ascent continued. She arrived at Mur de la Côte at 9:30 am and suffered more and more.

Mur de la Côte (John MacGregor, 1855)

She was out of breath, but she didnt give up. She asked her guides to help her to the summit, dead or alive. They supported her and they arrived at the peak. The lady pulled herself together, her pulse steadied to 108 BPM, and she felt revived. She took advantage of the moment to send a pigeon to the habitants of Chamonix, which didnt arrive, and to write to her friends. The guides helped her up to celebrate their victory. It was time to start the descent.

A Half-Hearted Posterity

The "fiancée of Mont Blanc" returned quickly to her hotel. Although she was treated with kindness and respect by its inhabitants, there were others who disparaged her, nonetheless. As Claire-Elaine Engel writes in her book A History of Mountaineering in the Alps:

"... She was a spinster who loved Mont Blanc because she didnt have anyone else to love

In 1838, the bizarre fantasies of the Baroness Dudevant, called Georges Sand in the literary world, enthralled the public: the Countess dAngeville was jealous of the other womans fame and maybe also of the mens clothing that she wore everywhere, even in Chamonix in 1836. Madame dAngeville completed her ascent of Mont Blanc, showing the world her virile courage, tendencies to hysteria, and a checkered woolen dress with baggy pants, a long coat, a wide beret with a plume, and a long black boa.

Strong words, but not very courteous and laced with flagrant sexism! The ladys name has nonetheless remained in the history books and she knew how to make herself a place in the pantheon of famous mountaineers. She died in 1871 after a life well-spent climbing numerous summits.

As for, Marie Paradis, she kept herself from boasting of her exploit, considering that she had reached the summit aided and even carried. After the ascent, she settled in the village above of Mur de La Côte and sold goods such as fruits, bread, and cream to mountaineers who followed the path to Mont Blanc. Her fame drew attention and she managed to make a living. She died in 1839 of dropsy.

The two women met after Henriettes return, first at a dinner to celebrate the victory in the company of their guides, and then just before Henriettes departure, when Henriette visited her Mont Blanc sister and Marie received her with great kindness. They shared a small snack of bread and butter, honey, and a pot of cream. Marie laid the table with a white tablecloth for this exceptional guest. The two women went their separate ways after one last talk, and never saw each other again.

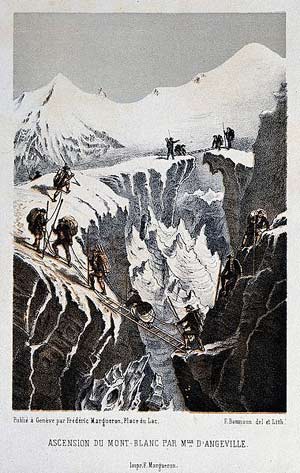

The ascent of Mont Blanc by Henriette dAngeville and her guides (Lithography by F. Bauman, 1838)

![Itinéraire indiqué sur un dessin issu du livre 'Souvenir du lac de Genève et ses environs : Vallée de Chamounie, Grand St. Bernard, Pont à Fribourg etc.', Le village de Chamouny : vers le Montblanc & le glacier de Bossons, vers 1860 (Swiss National Library [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)](image/mont_blanc_10.jpg)

The path followed by the two mountaineers

nathluli

Thanks to Lisa for the translation from the French to the English

www.mneseek.fr (partage de liens internet culturels)